Thousands wait to return home

By Gebre Egziabher Hadera, reporting for World Vision Sudan

Ton Doud is pretty sure he will miss the deadline.

He is planning to remain in an Internally Displaced Persons’ (IDP) camp along with the tens of thousands of other South Sudanese, long after camp long after the Sudanese government deadline to have left Sudan reaches.

“No one is supporting us,” the 63-year-old Ton complains.

Officially, the government is ordering all 500,000 southerners to leave or get their paperwork sorted out by May 20.

Yet, many people living in the camps in Sudan are worried about the escalating violence between the bordering countries and the uncertain future of life in South Sudan.

Before the camps

Ton was once a wealthy man before he fled from South Sudan with his three wives and one child some 29 years ago.

Ton was once a wealthy man before he fled from South Sudan with his three wives and one child some 29 years ago.

He had good income. He had a shop, a fishing boat, more than 100 cattle and 150 goats of his own. He was the chief of his tribe.

But then the fighting began. Clashes between Sudan People Liberation Army (SPLA) and Sudan Army Force (SAF), had a huge impact on Ton’s family. Five of his children disappeared. To this day, Ton is not sure if they are dead or alive.

What’s more, two of his relatives were killed.

Ton, his wives and remaining children decided to run.

“We were driven out from our village without a single property,” Ton remembers.

As well, on their scramble to escape, Ton’s four-year-old son died of thirst.

When he arrived in northern Sudan, the father of six had just one son left, along with his three wives. He was stripped of all his possessions. The future, he thought, was bleak.

Making a new life

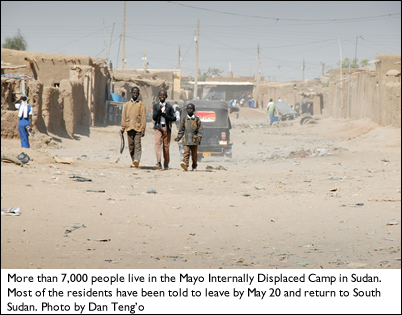

Inside the Moyo IDP camp, Ton and his family joined the 7,000 other South Sudanese living there. World Vision, who provides health, water and livelihood activities within the IDP camp, met Ton and his family here.

Ton tell World Vision staff that their family relied on donated food, clothes, housing and various programmes to carve a life for themselves in the camp.

While there, Ton fathered 11 more children. All but two are in school. His son Malek has entered college and is studying commerce.

What’s more, Ton has retained a sense of respect from the people in the camp. For more than 2,300 people who were from his tribe, Ton continues to be honoured as their chief.

As South Sudan gained independence last year, Ton, his family and the people from his tribe breathed a sigh of relief. Now, finally, maybe there would be peace. Maybe, he could return to his home.

Under orders to leave

As soon as South Sudan seceded, hostility grew towards those who remained in Sudan. Many South Sudanese who worked for the government were fired.

What’s more, the Sudanese government ordered all southerners out of the country, or to have proper paperwork, by April 8. Even those who were born in the northern part, but are deemed to be southerners, should either have proper paperwork or leave the country, were told.

Later, the Sudanese changed the deadline to May 5, and then again, to May 20.

In another scramble, some 15,000 people swarmed to the Sudanese riverside town of Kosti and hoped to catch a barge to return home.

According to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Sudan’s authorities refused to let the southerners travel by boat, citing security concerns, and instead insisted they travel by air. The first flights filled with

South Sudanese landed in Juba, the new country’s capital, on May 14.

And while some go, people like Ton are worried about leaving.

His relatives, who remained in South Sudan, tell him life in his former hometown is really hard.

“There is not enough food. No medical service, which makes life difficult especially for children. There are harmful insects, snakes and other wild animals which could put our lives at risk,” he says.

Meanwhile, his son Malek is worried that he’ll have to drop out of school.

“I’m happy to go back with my family, but I prefer to stay behind for a while until I finish my studies,” Malek says.

As the chief, Ton vows he’ll stay in the camp until all the people in his tribe have left. Then, and only then, will he be ready to go home.

“I feel as if I’m living in someone else’s house who is chasing you out. Your bad home is better than other’s good home,” he adds.