Generating Community Trust through Monitoring

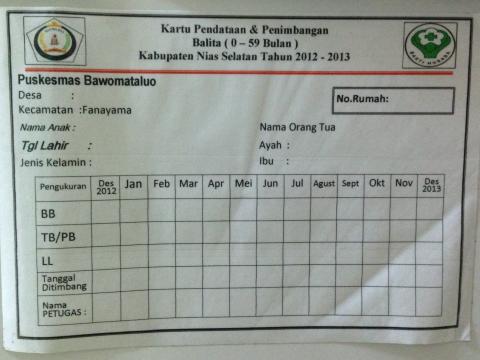

In South Nias district, there is a particular place called Bawomataluo where every house with a child under five has a sticker posted on the house, containing the information of the child’s weight, height, date of weighing, and this is updated routinely every month!

Perhaps this is something common for developed countries such as Singapore, but for Indonesia it is remarkable how one poor, remote area can achieve this timely and updated information of every child under five. Monitoring is one of common challenges in public health in Asia Pacific, and most remote areas will not have list of children under five, which then resulted in poor planning, low coverage of health services, and children fall through the cracks unnoticed and unknown.

Mrs Benedicta (36 years old) is the Chief of Bawomataluo Health Centre in South Nias District, a very poor area in the Nias island, near Sumatera island, west of Indonesia. This island was famous in 2005 when there was an 8.5 richter scale earthquake struck this remote island which caused Tsunami and killed 1,300 people. Nobody paid attention to Nias before the disaster, and people only knew Nias for its nice beaches to surf.

Mrs Benedicta and her team work with World Vision Indonesia’s South Nias to improve monitoring, starting with the inspiration to be able to work with accurate data. They only knew that coverage of health service was small and only a few children came to the Posyandu (Monthly Growth Monitoring & Promotion centre), but nobody really knew exactly how many children there were in the area.

This collaboration was started by taking opportunity of the Child Festival funded by World Vision Indonesia, where all children and their parents came to this big event, and the Health Centre used this golden opportunity to weigh all children under five, took the children’s pictures, and created for the first time a Baseline using real-time database.

Once they had this data of all children in the area, they stepped up to improve the monitoring by creating a village mapping. They worked together with the community volunteers and the midwives to plot the houses with baby, child under five, and pregnant women. This process was done in every village. So, for the first time they have a map for every village where they know which household has a young child or pregnant woman and its exact location.

In Nias, it is a custom to change the child’s name if the child gets sick. Imagine your frustration as a health worker if your list of children is different with the name of the children you have in the area just because they have their name changed! To overcome this problem, Mrs Benedicta and her team worked together with World Vision to create a database - not in the form of software, but as an actual book with child’s picture, date of birth, weight, height, and the nutritional status. This book helps them to overcome the custom of having different name of the same child, because they can match the picture of the child and it is routinely updated every month.

Not only in the book, each household with child under 5 or pregnant woman receive a sticker to be posted in the front door – this is as a household record of the child’s name and weight. This sticker enables health volunteer to follow up and do appropriate counselling, it’s also useful for World Vision to take the data for its sponsorship program in the Child Monitoring System. In the past, every child received a Child’s growth card. Unfortunately, mothers often lost the card, along with the data of the child’s weight. With this sticker system, it acts as a backup for the growth card, and the volunteers diligently write the weight, height nutritional status on the sticker and on the volunteer’s register book. If one household has 4 children under 5, there will be 4 stickers posted in their house.

Based on the village mapping, the community then decided together with the Health Centre the location of the Growth Monitoring centre (Posyandu). Now that they know the locations of houses with children under five, they can pick a place where there are a large number of children under five clustered together, and avoid picking a place convenient for the health staff but far away from the families.

Another good thing from the actual data and mapping is that they are now able to locate every child who is malnourished. Once the child is identified and located, the Health Centre can provide the appropriate interventions for the malnourished child.

For pregnant women, identification for pregnant women is also improved after the introduction of the baseline and mapping process. In Nias, pregnant women are usually discouraged for telling publicly about their pregnancies as it is a taboo. People usually know about it when the woman’s belly grows so big. With the sticker system, it helps as a discreet way to tell people that there is a pregnant woman in the house, and it’s very useful for the health worker and health volunteer to provide the health services and counselling. The Health Centre worked together with World Vision and the community on how to develop appropriate health promotion for the pregnant women and children under 5. The Village Midwives can follow up pregnant women better, and they made the pregnancy monitoring pockets, so that they can see how many mothers will give birth each month.

Mrs Benedicta confirmed that it is usually challenging to keep the Village Midwives in the remote areas. However, she shared some strategies that enable her to keep her Midwives working in the remote areas, such as:

- clear monthly action plan – reviewed by the Health Centre

- clear instruction for every task

- monthly meeting for sharing and learning

- supervision from the Health Centre

- clear and accurate data on target of children under five and pregnant women

- mentoring

- rewards to the midwives (what Mrs Benedicta meant by reward is actually inviting the village midwives to the village meeting in Health Centre and then she would be invited to share about the challenges in her area. Later on, her peers and the Health Centre will discuss together on the solutions. The same system also applies for the nurses, so they can take turn going to the Health Centre, and going to the city as a refreshing activity).

When asked about how to routinely and faithfully update the data, Mrs Benedicta shared that World Vision helped with some logistics including the scale for every village. She said that this will not be possible unless they have all the logistics in place. There is a special code for children who are above 5 years old and the child will be removed from the list. Since the book is a hardcopy, it can be easily added when there is new child under 5, and can be easily removed from the book by striking a line through the child’s name.

From these innovations, there are already some observable changes. In 2012 the number of children under five who came to Posyandu was only 54.9%, but in Jan-June 2013, there are 91.41% children who came, so there is 40% increase in the attendance of Posyandu within 6 months. Delivery with skilled birth attendant was 39.7% in 2012, but in the first semester of 2013 it’s 48%. In 2012, exclusive breastfeeding was practiced by 35.9% mothers, but within 6 months exclusive breastfeeding rose to 39.2%.

The mapping itself did not make the children under five come to the Posyandu, but it turned out that by conducting the Baseline, weighing all children, putting sticker in every house with children under five and pregnant women, the community members are convinced that the Health Centre and the ADP are serious in tackling the health and nutrition issues. The impact of this monitoring is not only on better data, better action, but also generating trust and cooperation from the community.* (VO/Esther Indriani, MCHN Specialist for South Asia and Pacific Region)