DREAMING OUT LOUD

Hopes and challenges facing girls around the world

GIRLS' FEARS, HOPES AND DREAMS

The stories below are from our most recent report offering a 2025 snapshot of the state of the world’s girls - told through their own voices. Grounded in United Nations data and other key sources, including World Vision’s recent survey of 432 girls across 51 countries, it reveals strikingly consistent themes. From Spain to the UK, Nepal to Peru, their candid insights highlight both shared struggles and universal hopes.

This report amplifies what girls want for their futures, not just a litany of problems. In amplifying their voices, we seek to honour the determination and resilience of girls worldwide.

Keep scrolling to hear and watch girls' stories or access full PDF report, here.

Around the world, girls are saying:

“We can achieve great things, if only you let us."

Use the map below to watch a video from a specific country included in our survey:

QUICK LINKS

Keep scrolling or click to jump to a section:

GIRLS FEAR INTERRUPTED EDUCATION

AND DREAM OF UNINTERRUPTED CHILDHOODS & ASPIRATIONAL CAREERS

Globally, 133 million girls are out of school.

Our survey revealed that one of girls’ fears is being pulled out of school simply because communities do not prioritise girls’ learning. One disruption to girls' education is child marriage - a social norm often rooted in the parents' belief that marriage will secure the girl’s future or relieve a financial burden. In most cases, when a girl is married off, her education typically ends.

“I’m taking an exam this year, and what scares me is the fear that my parents will decide to marry me off if I fail. I’m not mature enough for marriage right now.”

Unfortunately, her worry is well-founded. Family poverty and lack of options can result in girls being pressured to become wives when they are still children, robbing them of their youth and educational potential.

“If you are a girl and they have not taken you to school, your father can force you to marry someone who has more cows.”

In her context, bride price traditions (exchanging daughters for cattle or money) create a direct incentive to withdraw girls from school. She also noted, “Another issue is excessive work that exceeds your capacity,” referring to heavy household chores interfering with studies. Indeed, many girls must balance schooling with hours of housework or care for siblings, leaving little time for homework.

When marriage is not the reason, economic hardships often force girls to drop out. “I worry about my studies as my family’s condition is not very good. I worry if I will be able to pursue higher studies or not,” Preeti, 16, from Nepal told us.

“People around me often say, ‘What’s the benefit of educating a girl? Marry off the girl…’ This makes me feel that girls’ lives are truly difficult.”

Child marriage not only pulls girls out of school, it often leads to early pregnancy and health risks, effectively closing off pathways to the dreams they shared with us. On the flipside, educated girls marry later, have healthier children, earn higher incomes, and are more likely to reinvest in their families, breaking cycles of poverty.

“My dream when I grow up is to work hard to pass high school…go to university and become a doctor so I can help sick people.”

To honour such dreams, we must work to remove the obstacles – from child marriage to school fees – that continue to interrupt girls’ education.

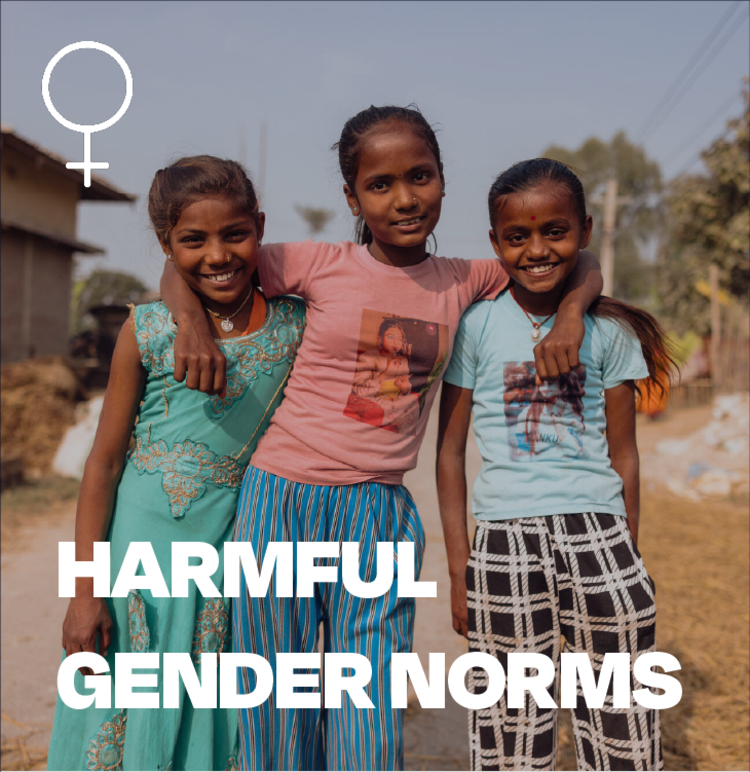

GIRLS FEAR HARMFUL GENDER NORMS

AND DREAM OF A WORLD WHERE THEY AREN'T HELD BACK, JUST BECAUSE THEY ARE A GIRL

Deep-rooted social norms and gender discrimination continue to limit girls’ potential worldwide.

One clear illustration is the burden of household chores. From an early age, girls are expected to cook, clean, fetch water, care for younger siblings, and more:

“The boys don't help us with housework. They're only here to eat.”

Globally, girls aged 5–14 spend 160 million more hours per day on unpaid care and domestic work than boys the same age. That is 40% more time spent on tasks that often go unrecognised but directly impact their ability to study or enjoy childhood.

Another harmful norm is the control over girls’ autonomy and decision-making. In many places, girls are not expected to have a say in important life decisions – whether it’s choosing a career, whom to marry, or even day-to-day choices like clothing and friendships:

“Many girls still can’t choose the careers they want, and their needs are often ignored. For example, girls are still forced into early marriages because it’s seen as tradition… These forced choices threaten their future and steal their dreams.”

Her words highlight a critical point: when a girl cannot direct her own life, she becomes trapped in roles others have decided for her.

Gender Stereotypes: Advantages & Dangers in Conflict Zones

The 11 girls who participated in this research from Democratic Republic of Congo all come from North Kivu in the Eastern region of the country, where armed groups have recently taken control. Several of the girls cited their gender as an advantage, because it helped them to escape forced recruitment into armed groups:

"The moment that makes me proud to be a girl is when armed men come to take the young boys and leave us girls behind."

However, others cited the double edged sword of these gender roles:

"Sometimes I think that life would be rosy if I had been born a boy because when we go to the fields we come across armed men who rape the girls and leave the boys…I think to myself that I would have liked to be a boy."

Their worries are unfortunately reflected in the latest UN statistics on sexual violence, which highlighted a surge in sexual violence in Eastern Congo that mirrored the spike in conflict. Girls living in conflict-affected contexts experience additional vulnerabilities which exasperate existing social norms and prejudices.

GIRLS FEAR VIOLENCE & ABUSE

AND HOPE FOR A DAY THEY FEEL SAFE & ARE TREATED WITH DIGNITY

Fear of violence and abuse is - for many - the worst part of being a girl.

Violence against girls remains pervasive, taking many forms: bullying in schools, sexual harassment on the streets, beatings in the home, trafficking and rape in conflict zones, and online abuse, to name a few.

“The hardest thing about being a girl is being exposed to bad behaviour – harassment and rape – which are common among girls right now.”

It is chilling that she speaks of rape as a common threat “among girls right now.” Unfortunately, global data supports her perception. Around the world, 1 in 8 girls has experienced forced sexual violence.

Elisneith, an 11-year-old in Colombia echoed similar worries:

“The worst is that there are people who harass children or kidnap them… Some mothers are even afraid inside their own homes, because someone could come and take their children away.”

Her fear of kidnapping and harassment is a reality in many places – whether it’s the risk of human trafficking or abuse by someone in the community.

Violence in its many forms leaves lasting scars:

“The worst part of being a girl is that boys sometimes bully us because they think girls are weak.”

Indeed, one in three students globally experiences bullying in school. Such a climate of fear and intimidation erodes girls’ confidence and mental health, and can keep them from fully participating in school or community life.

It must be emphasised that violence is not a “girls’ issue” – it is a societal issue. Girls are targeted precisely because perpetrators (mostly men or boys) are able to act with impunity, driven by norms that have tolerated violence against women and children. To protect girls, we need both strong laws and effective enforcement, as well as norm change.

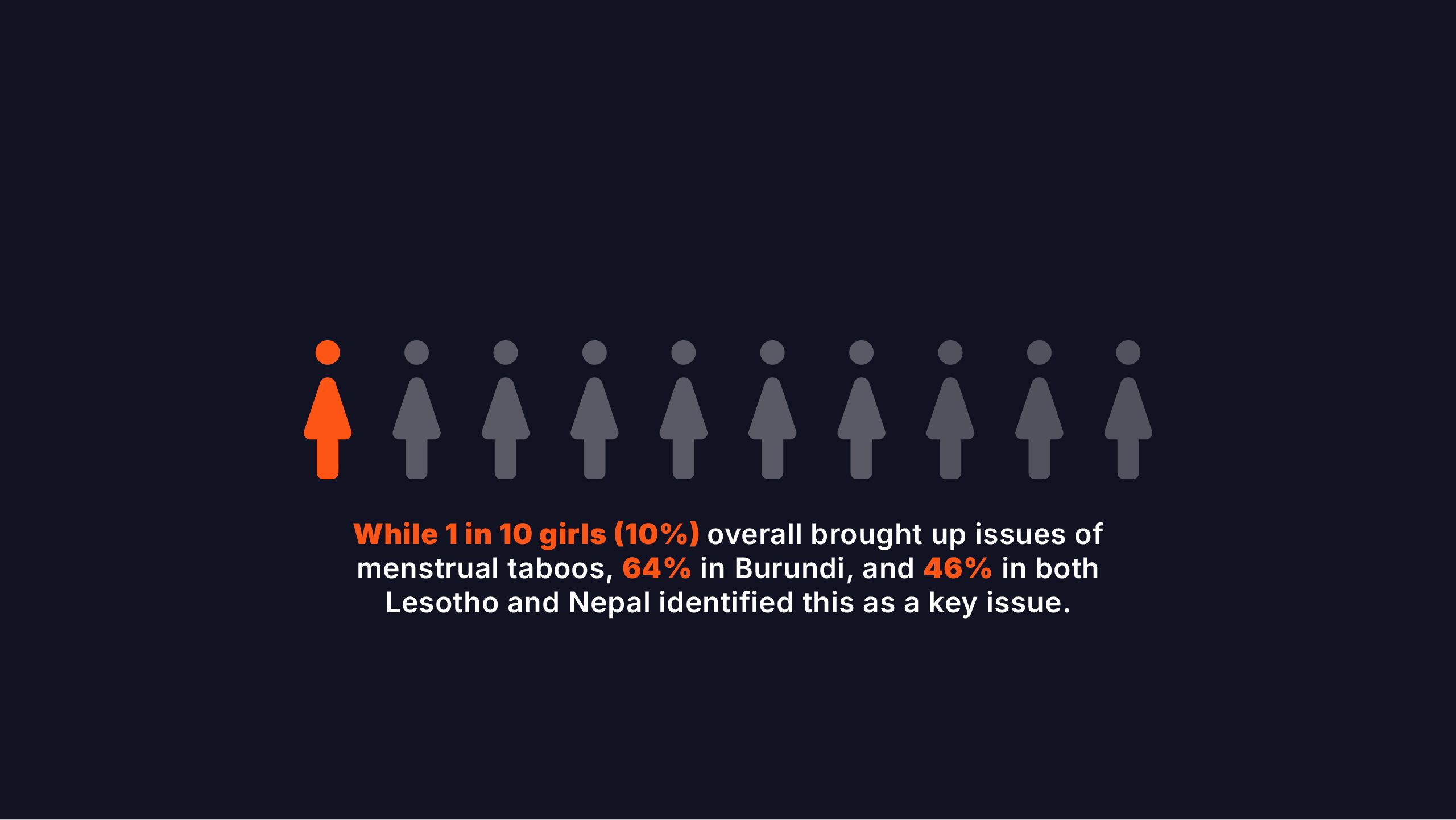

GIRLS FEAR SHAMEFUL MENSTRUAL STIGMA

AND DREAM OF ACCESS TO MENSTRUAL HYGIENE PRODUCTS

For millions of girls, getting their first period ushers in new challenges and stigma.

Menstrual stigma and lack of sanitary support are causing girls to miss school and feel ashamed. In many countries, menstruation is shrouded in taboo, and inadequate facilities make it hard for girls to manage periods with dignity.

Beyond the cramps and inconvenience, it’s the social treatment during menstruation that really troubled them:

“We are hidden when we are on our period – not allowed to go out of the house, and others cannot touch the things we have touched. That is the worst part for me.”

In parts of Nepal (and elsewhere), menstruating girls and women are considered “impure” and are isolated – sometimes even made to sleep in a shed.

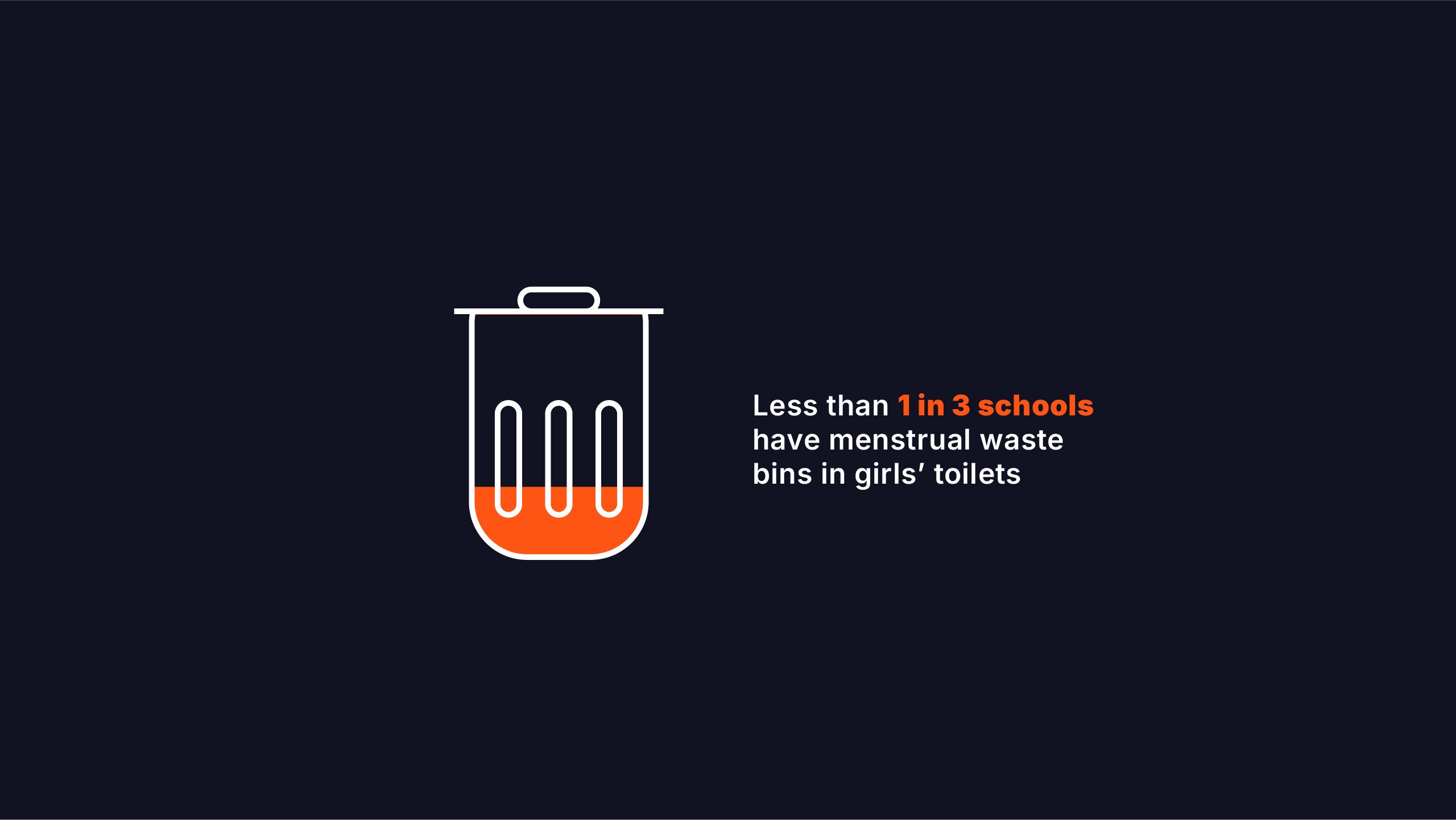

Physical pain and social stigma aside, the practical challenges are just as serious:

“My school doesn’t have bathrooms.”

“What disgusts us as girls is not having sanitary pads during our menstrual periods.”

These strong words – angry, disgusted – highlight how indignity around menstruation affects girls emotionally. Lacking proper menstrual products often leads to girls missing school days every month. They fear leakage and humiliation, or they simply cannot manage their period at school if there’s no water or privacy.

Phimchai, an 11-year-old from Laos, shared a simple wish:

“My hope and dream are to have a toilet and clean water system at school.”

We cannot allow the shame and logistical barriers to continue to undermine girls' educational progess by missing class. An innovative World Vision programme in Zimbabwe, funded by the UK Government, previously helped address this and other barriers to girls’ education through a nine-part strategy that saw community leaders and men help make reusable pads for their girls and advocate for their inclusion in school, among other activities.

GIRLS FEAR CONFLICT AND ECONOMIC HARDSHIPS

AND DREAM OF A LIFE FREE FROM FEAR AND TRAUMA

Girls are taking on economic worries and dealing with the weight of conflict.

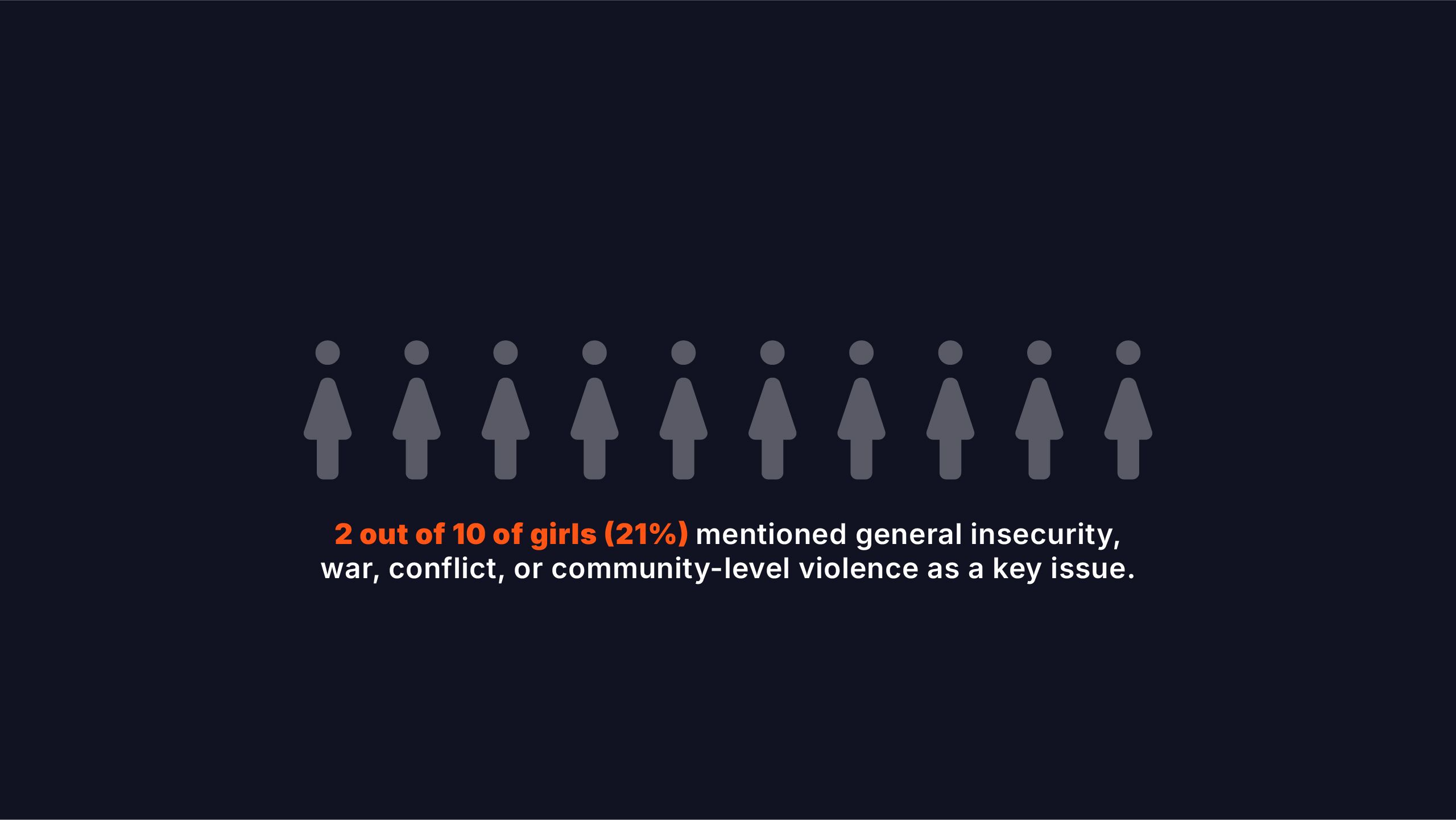

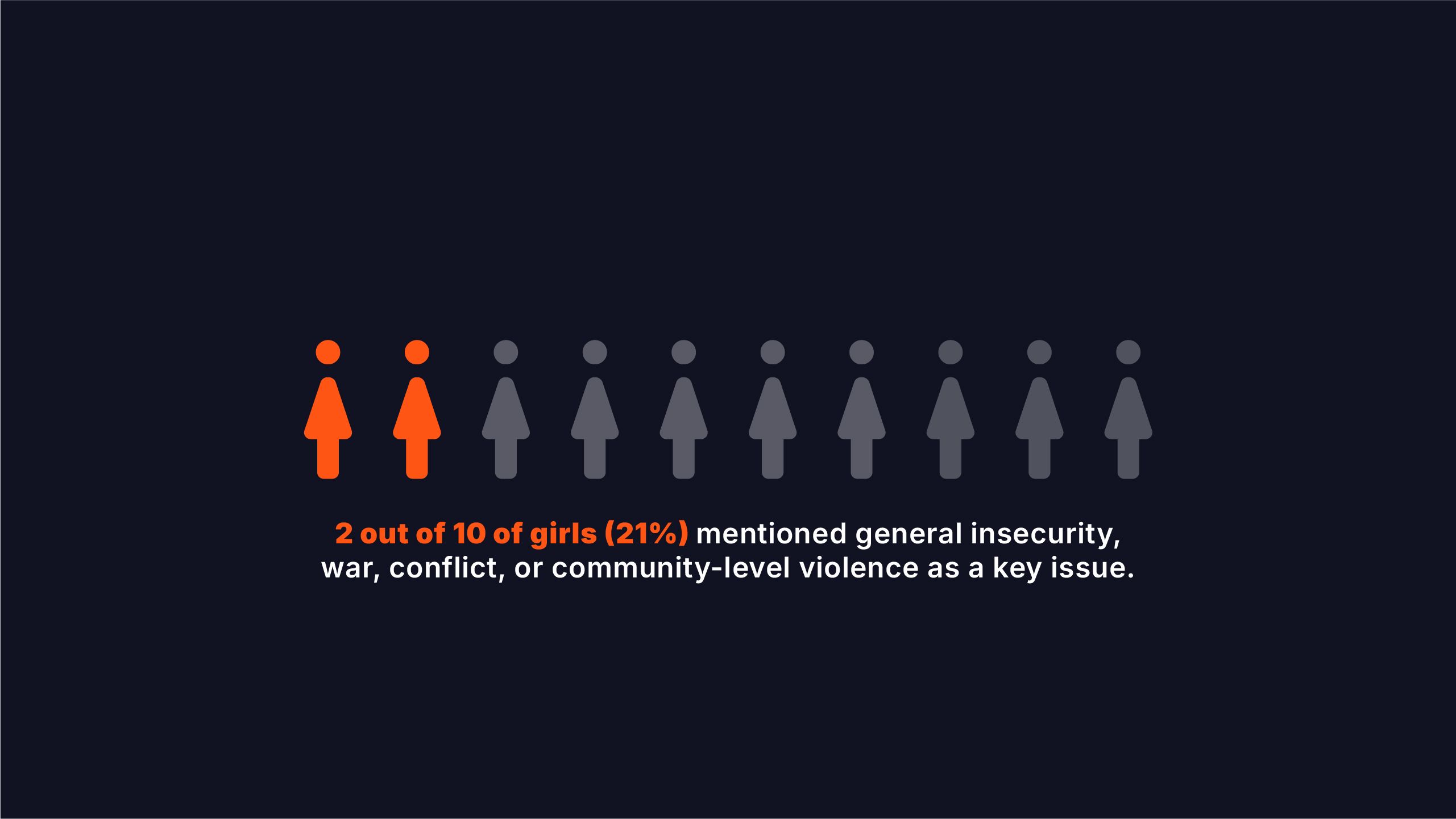

Although their gender does play a role in the worries of many of the girls we spoke with, many of them also reflect broader crises and difficulties in their societies. Girls repeatedly mentioned economic hardship (especially rising food prices) and conflict or insecurity in their interviews.

Food insecurity emerged as the single largest economic concern:

"I worry about the lack of food, people here in the village do not have food, they need food and die of hunger."

The highest numbers of girls mentioning hunger and food were in Peru and El Salvador, where our 2024 food price survey found it would take more than 12 hours work to earn enough to buy a basic food basket, more than four times the equivalent in Spain or New Zealand.

Beyond economic pressures, conflict and insecurity create an environment where girls consistently report that conflict makes their gender identity itself a liability and impacts their mental health.

Constant fear, witnessing violence, and trauma is a relentless attack on the mental well-being of girls:

“My niece…started crying. She didn’t want to go back to school because she was afraid. It was very traumatic. Sometimes classes get canceled because of shootings or gang fights…You can become a victim even if you have nothing to do with it.”

We heard girls mentioning being afraid of the dark or loud noises. Sandra, 17, from DRC, describes the relentless nature of conflict:

“Every day is war. Not a year goes by without displacement and families are becoming poorer because of this.”

It’s important to note that conflict and economic problems are often intertwined. War drives inflation and hunger (as we saw with Ukraine’s war affecting grain supplies), and conversely, desperate economic conditions can fuel conflict by driving competition over limited resources. For girls, these issues compound. For example, in a famine caused by conflict, a girl might face starvation (economic issue) and risk of being trafficked or assaulted (security issue) if she travels to find food.

“The future I want for all girls is one where they are free, fearless, and fully seen. Where every girl has the right to dream big, to be educated, to lead, and to live without fear.”

It is time to match their courage with our commitment.

THERE IS HOPE.

Our most striking finding is that 84% of girls express hope - not naive optimism, but complex, multidimensional hope that encompasses dreams, strength, compassion, joy, and wisdom.

23% OF GIRLS

Nearly all girls articulate clear dreams and aspirations. They want careers that help others - doctors, teachers, nurses, engineers.

"My dream is to become an engineer, and I hope to achieve my dream one day so that I can inspire others."

— Saeeda, 13, from Afghanistan, despite currently living under increasing restrictions on her aspirations

43% OF GIRLS

Girls demonstrate remarkable strength, with 100% resilience in the most challenging contexts.

"Palestinian girls are strong. I wish they could all receive full education, but unfortunately many cannot, yet they are still trying to break through the barriers."

— Shaam, 11, from the West Bank

30% OF GIRLS

The desire to help others drives many girls' ambitions.

"My dream is to be a doctor so I can help my community and those who need my help."

— Faith, 11, from the Philippines

43% OF GIRLS

Despite hardships, girls find happiness and gratitude.

"What makes me happy is to see girls attending schools and performing better than boys."

— Roselyne, 17, from Burundi

47% OF GIRLS

Girls demonstrate profound understanding of self-worth and dignity.

"The future I'd love to see for all girls is one filled with safety. I want a world where no girl is afraid to speak or dream. A world where we are respected fully."

— Ami, 13, from Albania

NOT A COUNSEL OF DESPAIR, BUT A CALL TO ACTION..