Rohingya refugee children deserve to go back to school, too

Loud giggles announce the arrival of 30 excited children eager to start their day at World Vision’s child-friendly space here in this refugee camp.

Eleven-year-olds Taslima and Yacob and their friends flock through the doors.

"Let’s settle down for attendance," says Adbul Bashar, the centre’s facilitator.

As Adbul calls out names, Taslima clusters in the corner with her friends. Yacob rushes to occupy his self-designated space.

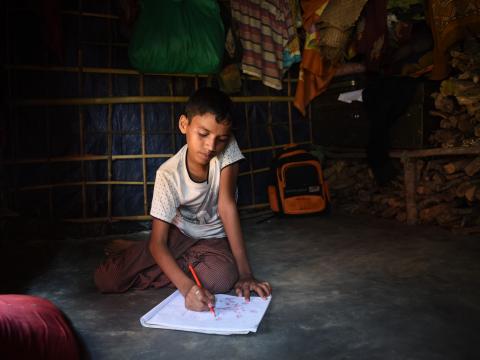

Abdul begins the day with storytelling and drawing exercises. With a rainbow of coloured pencils, the children transform crisp white sheets of paper into vibrant works of art.

"Let’s pack up the crayons now," says Abdul. “It’s play time.”

Yacob whispers to Zaibul, pointing to a rack of balls. Yacob leads a group of boys who run to grab their favourites.

Across the room, Taslima gently places a carom board on the floor and invites three girls to join her in a game.

"We didn't have this game in Myanmar,” says Taslima. “I like playing it here. It’s fun.”

Taslima and Yacob have been daily regulars at the centre since fleeing their homes in Myanmar one year ago. Last August, a wave of violence in Rakhine State following decades of discrimination and systematic human rights violations sparked a mass exodus of 706,000 Rohingya—a predominately Muslim ethnic group. Today, Taslima and Yacob live in the world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh— now home to 890,000 refugees. More than half are children.

“This has been the most memorable year of my life,” confides Yacob. “When I came to this country, I was sad because my family lost everything we had in Myanmar. We had nothing to start our lives again with.”

One of nine children, Yacob and his family saw their home torched as ran from their village under mortar fire. They walked for days without food to reach Bangladesh. They arrived hungry, thankful to be alive, to be together.

Getting her children safely across the Naf River to the shores of Bangladesh is an ordeal that Yacob’s mother, Nurankish, 41, will never forget.

"I solely depended on God to get our family through that,” says Nurankish. “I kept telling my children not to leave my sight for a minute. We had to be on guard all the time.” Nurankish says being uprooted from all that was familiar—their home, school and friends—terrified the children. They said little, but she saw the worry on their young faces.

“It was a new place for them and everything was unfamiliar,” says Nurankish. “As a parent, you fear for your children’s future. You start thinking, ‘What will become of them?’ I could see what our situation was doing them.”

Yacob listens to his mother describe their early days in the camp, seated cross-legged on the concrete floor of the family’s sweltering one-room bamboo shelter. “In Myanmar, I used to go to school. I was in Grade 2 when we left. We studied Burmese literature in our class. When we came here, we had nothing much to do. I stayed at home mostly.”

In October 2017, World Vision opened its first child-friendly space (CFS) near Yacob’s home. Today, World Vision runs 12 child-friendly spaces for children aged 5-12 in the camps. Over 1,700 are enrolled at centres. While the CFS does not offer formal education, they are safe, fun places where children can play, learn and regain a sense normalcy in their disrupted lives.

Initially, refugee parents hesitated to send their children to the centres run by strangers—World Vision Bangladesh staff and volunteers from the local community.

“There was a sense of fear,” says Abdul, the CFS facilitator. “Most children had experienced or witnessed violence of some kind. They stayed indoors with their parents and didn't come out. We went house-to-house with the majhi (refugee community leader), informing parents about the purpose of the CFS. We shared about the importance of learning and how it will help their children grow. Gradually, the children started coming to the centres.”

Education was never a given for children in Myanmar. According to the Oxford Burma Alliance, a student-run organisation at Oxford University, more than 60 percent of Rohingya cshildren between the ages of five and 17 have never been to school due to poverty, government restrictions on their movement, and a lack of schools in Rakhine State, Myanmar.

Among Rohinya adults in the camps, the illiteracy rate is reported to be as high as 80 percent.

"People living here were farmers, fisher folk and petty business owners back in Myanmar,” says Mohammed Salim, 20, a majhi in Camp 19. “Education was never prioritised for us. Finishing school and going to university was an unattainable goal. Only a few of the children here have studied until Grade 4.”

A recent education report by the UN Inter-Sector Coordination Group confirms this. It revealed that prior to their displacement, only 50 percent of girls and 58 percent of boys age 8 and older in the camps reported graduating from at least Grade 1 in Myanmar’s school system.

Those who had greater access to education completed three grades of schooling on average, with 31percent of boys and 25 percent of girls having completed Grade 3.

On a positive note, according to the report 51 percent of children who have never previously attended school have started attending a learning facility, such as a World Vision CFS, since arriving in the camps.

Yacob has hardly missed a day since the CFS opened near his home last year. “I come here because I like to learn. I want to become a teacher when I grow up,” says Yacob, a natural leader who enjoys organizing games and group singing at the centre.

Nurankish has noticed positive changes in her son. “When Yacob comes back from the centre, he shares with me what he learned,” she says, smiling proudly. “The whole struggle of leaving our home in Myanmar affected him and my other children, but I see them getting better now. Sending them to the centre helps because they get to learn and play with other children. It has helped them overcome their worries. They are slowly getting back to feeling normal again. I want a bright future for my children where they can be what they want to be.”

Like most parents, Nuruankish wants the best for Yacob and her children. But in the camps, education options are limited. While the CFS provide a few hours of daily recreation, teaching important skills like reading and writing that children need for a brighter future is restricted.

The Rohinyga here are not officially recognised as refugees. Without such status, their rights under the 1951 Refugee Convention are not protected, including the right to education.

Currently, some 400,000 children and youth in the camps are not receiving any formal education. Adolescents are particularly at risk: Less than 2,000 adolescents out of the 117,000 in need have access to education or life skills training.

“These Rohingya children risk becoming a lost generation,” says James Kamira, World Vision’s child protection specialist. “Without the protection of being in school, these children are increasingly vulnerable to child marriage, forced labour, trafficking and radicalisation.”

Many refugee parents don’t send their children the CFS because they need them to help out at home. “There is a mindset in the community that learning is only valuable for children under age 12,” explains James.

When Yacob turns 12 later this year, he may be expected to start working, gathering firewood with his two older brothers, 13 and 16. The 300 taka (USD$4.00) they can earn a day carrying bricks takes precedence over going to any learning centre.

“Income is an issue for us,” says Nurankish. “To survive, we need to make a living so someone needs to work. But we are open to sending the boys for any training that ensures better opportunities.”

Adolescent girls in the camps have even fewer opportunities for education. Parents keep them home for fear of them being assaulted in the camps, where incidence of gender-based violence is high. Cultural norms prevent girls from mixing with the opposite sex, and segregated classrooms are not available in the few learning centres for youth. So while 11-year-old Taslima enjoys attending the CFS, her older sister, Yajurjanat, 13, stays home.

“I want to study, but I cannot because I am too old and not eligible for school,” says Yajurjanat, who spends her days sweeping family’s small shelter, fetching water and helping her mother cook.

The girls’ mother, Humaira, 30, wants her daughters to get an education. “I got married when I was 13, but I don't want that for them,” she says. “Taslima likes going to the centre. She has become more confident in her speech and become smarter. Her mind is sharp and she loves to learn new things. Education is important because it will teach her to take care of herself. One thing I need for my child is the opportunity to study.”

Taslima, like Yacob, wants to be a teacher, too. “I love children,” she says confidently, looking up from her notebook lined with numbers and English sentences. “I need to study so that I can teach children from our community when I grow up and help other people.”

Increasingly, Rohingya parents in the camps are recognizing the value of schooling and appealing for access to education for their children. In their support, World Vision is urging the Government of Bangladesh to reach more children with high-quality, inclusive education for all children in the camps.

"Education brings respect,” says Nurankish. “We have options to choose from if we are educated. I want Yacob to study further. He is our hope to become something greater and dream bigger.”

Written by Annila Harris | Edited by Karen Homer | Photos by Annila Harris