Beyond Pills: How to End Neglected Tropical Diseases

Dr Eun Seok Kim, infectious disease physician and Health Specialist with World Vision, says NTD elimination requires more than drugs. Evidence from Uganda’s MANE project shows lasting change comes from safer environments, engaged communities, and resilient health systems.

26 January 2026

Several years ago, while working as a visiting physician in Uganda, I met a patient I never expected to see in the endoscopy unit of Kiruddu Hospital in Kampala. He was in his early twenties and experiencing severe internal bleeding in his oesophagus.

The cause was not alcohol use, cancer, or viral hepatitis. It was schistosomiasis – a disease caused by parasites in contaminated freshwater – which he had unknowingly acquired as a child while fetching water and swimming in Lake Victoria. One of its most serious long-term effects is internal bleeding that often goes unnoticed until it becomes life-threatening.

That encounter stayed with me. I learned that nearly 1.5 billion people worldwide are affected by one or more neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). In Uganda alone, almost half the population lives in environments where the risk of NTD infection remains high. These realities led to my involvement in the design and launch of an NTD elimination initiative in Mayuge District, eastern Uganda.

Why have NTDs persisted despite years of treatment?

Since 2003, Uganda has implemented annual mass drug administration campaigns for NTDs, including schistosomiasis and intestinal worm infections. Supported by the Ministry of Health and World Health Organisation, medicines have been distributed through government systems and NGOs, including World Vision.

Yet more than two decades later, infections – particularly schistosomiasis and hookworm – remain stubbornly prevalent in districts such as Mayuge.

Between 2019 and 2022, World Vision implemented the Mayuge NTD Elimination (MANE) project with funding from the Korean International Cooperation Agency. The project went beyond treatment alone, combining drug administration with water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions, community engagement, and health system strengthening.

To understand why transmission persisted, World Vision conducted field research among school-aged children.

The findings were clear: after more than 15 years of treatment, ongoing infection was driven not by drug failure, but by repeated reinfection.

What the data revealed about daily life and reinfection

Analysis of reinfection risk factors showed that NTD transmission was closely linked to everyday living conditions.

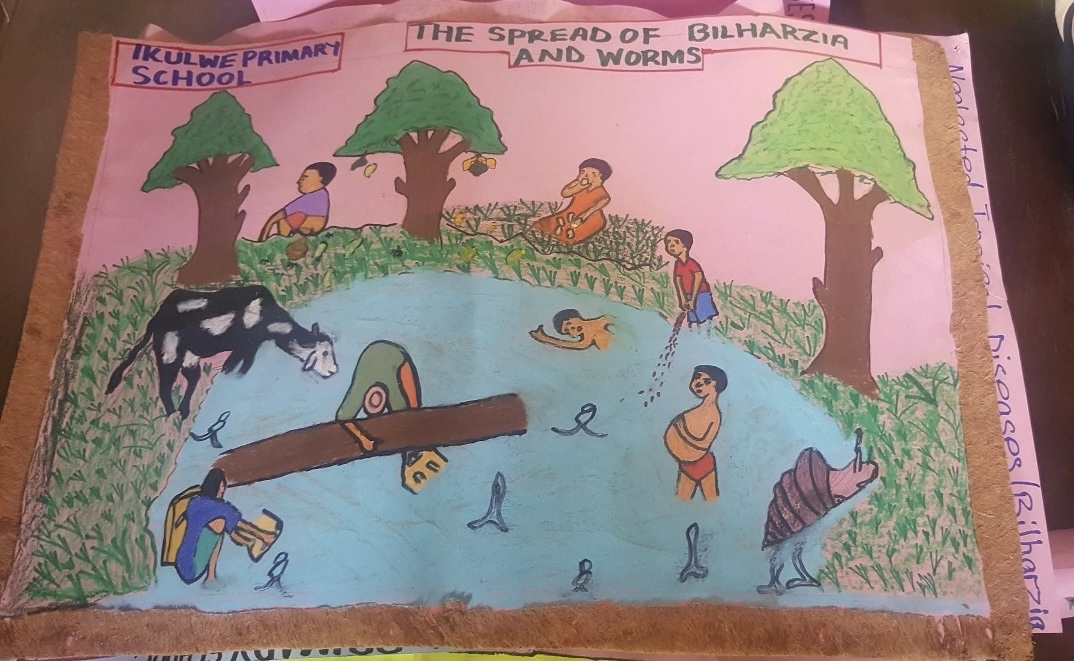

Children who spent more than 30 minutes fetching water faced significantly higher risks of hookworm infection. Those who regularly worked barefoot in soil were also more vulnerable. For schistosomiasis, the strongest links to reinfection were living near bodies of water, frequent swimming or bathing in lakes and rivers, and poor hand hygiene.

In short, children’s daily routines – shaped by poverty, geography, and infrastructure gaps – were sustaining transmission.

These findings underscore a critical reality: NTD elimination cannot be achieved through drug distribution alone. Without changes to the environments and behaviours that drive exposure, reinfection will continue.

A shift grounded in evidence: The MANE approach

The research confirmed what communities had long experienced: to eliminate NTDs, the conditions that allow infection must change.

In response, the MANE project strengthened an integrated, people-centred approach that combined mass drug administration with improved access to safe water and sanitation. Community-Led Total Sanitation, education and behaviour-change activities, and stronger local diagnostic, surveillance, and health information systems.

At its core, the project moved away from viewing people as passive recipients of medicine, and instead supporting communities as agents of change, while also strengthening the health systems required for sustainable prevention, diagnosis, and care.

Why awareness and behaviour change mattered

During design and implementation, the project uncovered a critical gap. Despite years of deworming campaigns, many community members had limited understanding of how NTDs are transmitted or prevented. Schistosomiasis, in particular, was often attributed to witchcraft, leading some families to seek traditional rituals rather than medical care.

This highlighted the need for tailored education strategies for both children and adults.

Through school-based activities – clubs, quizzes, and inter-school competitions – children began to understand the link between everyday behaviours and health outcomes. These messages travelled home, and children became advocates for healthier practices within their families.

For adults, World Vision’s Citizen Voice and Action platform supported accurate understanding of disease and enabled dialogue with local authorities. Together, communities and leaders worked to improve living environments and expand access to WASH facilities.

What does ‘elimination’ really mean?

NTDs thrive where poverty, fragile systems, and environmental exposure intersect.

Elimination, therefore, is not simply about lowering infection rates. It is about transforming the lives of children and communities at risk, strengthening the health systems that serve them, and improving the environments that sustain vulnerability.

The experience in Mayuge delivers a clear message. NTDs can be eliminated – but not simply by distributing more pills for longer periods. Elimination becomes possible only when daily lives change, enabling environments improve, and health systems are strengthened alongside communities.

NTDs have persisted among people living in the most marginalised and difficult conditions, often in silence. Breaking that silence begins with listening to voices in communities – and with moving beyond pills to respond responsibly to people’s lives, environments, and the health systems that sustain them.

_______________________________________

Dr Eun Seok Kim is a public health specialist and infectious disease physician, serving as a Health Specialist with World Vision and as Project Director of the VIDA Project, a climate-resilient health system-strengthening initiative in the Amazon regions of Peru and Bolivia.

He has worked clinically in Korea, Peru, Malawi, and Uganda, and has led programmes in maternal and child health, NTD elimination, HIV/AIDS prevention, malaria and dengue control, and health systems strengthening, with a strong focus on evidence-based, people-centred approaches.