Hunger in West Africa: Putting you in their shoes.

You are in a small health clinic in the South of Chad, in West Africa. It is 9 am. The air is hot, dry, filled with cries.

You are in a small health clinic in the South of Chad, in West Africa. It is 9 am. The air is hot, dry, filled with cries.

You are amidst 40 mothers, sitting on the ground or on the clinic’s porch, babies in their laps. Under brightly coloured headscarves, their faces look tired, drawn, sad. You catch glimpses of the babies. Their skin is stretched over their chests like paper over wire frames. Their legs are long and thin. Their bellies are protruding.

Four of the mothers, clearly malnourished themselves but still trying to breastfeed their babies, are sitting on a wooden bench on the porch. In front of them, a row of tall, red roses. You have never seen so much colour and sadness in the same place. The contrast is unbearable. But you try to cope.

Then your name is called out. You look up. But it’s not you who is being called. It is one of the mothers. She struggles to get onto her feet. She walks with her baby into the consultation room. Tears flow down the baby’s face as he is being measured, weighed, and the nutrition monitoring armband is wrapped around his arm. You don’t need to wait to hear the results to know he is severely malnourished.

You ask your namesake about her age. “I think I was born in 1990, and my baby is about one now,” she says, tugging gently at her baby’s purple hat, trying to sooth his cries.

Then it hits you. You share the same name. But your lives couldn’t be more different. Or your worries. Yours revolve around the fear that the engulfing sadness around you would trap and render you useless, unable to do your job. Hers are centred on the sick, fragile little boy she is holding in her arms.

In this small health clinic, 39 other mothers share the same worries. “Priscille”… ”Marie” …. Names keep being called out. But the verdict is the same each time: severely malnourished.

Thirteen million West Africans are suffering

In West Africa (Niger, Mali, Mauritania, Chad and Senegal) about 13 million people share similar worries. The lack of rain last year, the failed crops, the rising food prices and declining food stocks, the cycle of drought that has been hitting the region, have rendered entire families and communities vulnerable. “I can’t even look after myself, how I can look after my baby?” says another of the mothers at the clinic in Chad.

More and more people are resorting to desperate measures: leaving their villages, their families and migrating to cities to work or to beg; surviving on wild fruits or animal feed; selling their animals – their only livelihoods – even though their price is getting lower whilst food prices are getting higher, in some areas up to 100 per cent.

Why should we help?

And this is why we are here. And by “we”, I don’t mean the larger World Vision team. I mean “you” and “me”. And everyone we know. Everyone who might have a namesake in this part of the world. A namesake that is almost certainly less lucky than us. Just because he or she happened to be born in a land without rain, without food – in the world’s poorest region.

And this is why we are here. And by “we”, I don’t mean the larger World Vision team. I mean “you” and “me”. And everyone we know. Everyone who might have a namesake in this part of the world. A namesake that is almost certainly less lucky than us. Just because he or she happened to be born in a land without rain, without food – in the world’s poorest region.

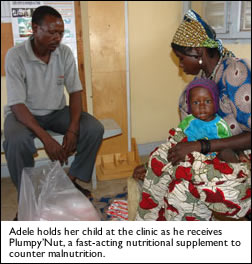

And there is a sense of comfort in us being here. In the power of humanitarianism. In this quality – inherent in all of us – which, when exercised, feels entirely right. Because it’s the number of eyes, ears, hands and hearts that make it possible for mothers like Adele and their babies to get help and feel safe. And this is why you and I, and everyone we know, should be here.

And because although hunger is number one on the list of the world’s top 10 health risks – killing more people every year than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined – it is also the single biggest solvable problem facing the world today. We just need to be there. Here.