It’s not up to AI to plan just and child-friendly smart cities

For #WorldCitiesDay Aline argues that smart cities aren’t built with sensors and data alone, but with empathy, inclusion, and justice.

Cities at a Crossroads

I live in what is considered a people-centred smart city. Toronto is well-known for embracing technology and innovation to improve urban living and services. In Toronto, traffic lights are AI powered to adjust based on real time traffic data contributing to improve traffic flow. Digital permits and mobile-friendly services make it easier for all residents, especially caregivers with fulltime jobs, to access city services more efficiently. A lot of the city residents’ engagement in public meetings on plans, programs and budgets happen online through surveys and online platforms making it accessible for the majority to give feedback and input into the city planning.

In December, I will go spend a month at home in my city of birth, Beirut, where like in many cities of the Global Majority countries, such infrastructure is not yet set up for an improved urban life. Leaving technology and innovation aside, many things we take for granted in Toronto’s relatively people-centred built environment are absent in Beirut, such as the wide sidewalks, intergenerational public parks, public libraries and public transit.

Yet, cities around the world, including both Toronto and Beirut, are currently faced with global urban challenges that such infrastructure could help address effectively, if not prevent. The theme of 2025’s World Cities Day “People Centred Smart Cities” is what I think of as an aspirational theme aiming to get the cities of the world where they need to be in order to address the megatrends that are shaping over the next quarter century: demographic transitions, climate and environmental crises and frontier technologies.

Yes, building smart cities is critical in the face of the challenges we are currently facing, but smart cities are not just tech-driven; they are also child-centred, inclusive and resilient. Whether through prioritising safe and accessible public spaces, or ensuring children and caregivers, regardless of status or race, can access essential services, or by promoting children’s participation in urban planning and budgeting through our social accountability work, our urban work in World Vision offices across the globe is geared toward making cities work for their youngest citizens.

Smart cities must be just cities

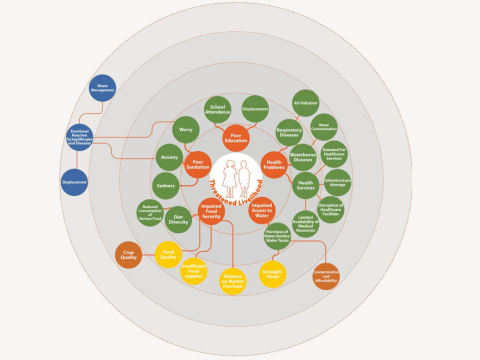

In cities of the Global Majority countries, marginalisation and inequity are on the rise. Over 1 billion people live in urban slums where proximity to services does not necessarily guarantee access. Access to resources, services, facilities and opportunities is inequitable in those urban environments. In the inadequate housing conditions of urban slums and informal settlements, privacy becomes an unachievable luxury, and public and safe spaces are absent. In a world where better resourced cities are using AI and advanced technology to improve urban life, the social, economic and digital divide becomes more glaring where in basic rights are not guaranteed where the Majority Population lives.

Climate change has been dubbed as the great equalizer in the sense that it puts everyone at risk, regardless of where they live. Yet, children are bearing the greatest burden of climate risks as climate change amplifies existing vulnerabilities and inequalities (including those based on age, gender, class, ethnicity, ability and land rights). Our publication Just and Resilient Cities for Children supports our argument that smart cities must also be equitable, safe, and responsive to children’s needs and highlights how digital innovation, when paired with inclusive governance, can advance justice and resilience. Our work on the Thrive project in Dhaka, shows how using digital tools and innovation can enhance urban resilience and justice.

Nature-Based Solutions as smart urban innovation

Smart city planning requires urgent attention to the growing climate risks that are increasing urban fragility. Rapid and unplanned urbanisation, especially in Majority Population counties that fall within low- and middle-income categories, is exacerbating the pressure on natural ecosystems and driving cities into high-risk zones (such as floodplains and coastal areas), intensely increasing exposure to climate-related hazards. This is where our work on Regreening Communities in urban contexts through nature-based solutions (NbS) becomes an important contribution and “a powerful entry point to address root causes of vulnerability – including climate change mitigation – while delivering co-benefits across environmental, social and economic domains.”

NbS are low-tech but high-impact solutions that improve urban ecosystems and community well-being. Whether we support urban gardening in Vanuatu or waste management and livelihoods in Philippines, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, or implementing tiny forests or mandala gardens, we are:

- Empowering citizens to transform underutilised spaces into productive green areas, fostering local innovation and digital storytelling for awareness,

- Integrating community-led monitoring, digital knowledge hubs, and cross-border collaboration for scalable urban sustainability, and

- Enhancing urban livability and child well-being through accessible green spaces and 4) contributing to urban cooling, ecosystem restoration, and community pride.

Smart cities tackle pollution for children’s health

Data and partnerships can drive smart responses to environmental health risks in cities. Our work through a multi-stakeholder partnership model in Dhaka, Bangladesh bringing together Dhaka North City Corporation (local government), the Centre for Atmospheric Pollution Studies or CAPS (research institution) and the Dhaka North Community Town Federation (civil society), allowed us to address the pressing issue of air pollution which is significantly impacting the health of children as well as other vulnerable groups in the megacity. Our case study “Tackling Air Pollution for Children’s Health and Wellbeing in Urban Bangladesh” illustrates the use of data for evidence-bases action as well as the community-led monitoring and advocacy through citizen-led air quality monitoring, public forums and dialogues to influence policy and integrate air pollution mitigation in city development plans.

Smart cities as platforms for citizens’ voices

Smart cities as platforms for citizens’ voices

Social accountability is at the heart of our work in World Vision across the rural-urban continuum; we equip citizens with tools and resources to advocate for their own rights, leading to more sustainable outcomes of the work we do. Increasingly, in our urban programming work we have been expanding the use of digital tools to facilitate citizen-led monitoring of services like health, education and sanitation as well as to promote youth-led digital advocacy. Two case studies from our work on social accountability in urban contexts in Mali and Bangladesh highlight how those mechanisms are not just technological innovations, but they are smart tools for urban accountability that play a major role in ensuring that city planning and governance respond to the needs and feedback of residents, including the most marginalised and the most vulnerable.

Toward people-centred smart cities for children

As I prepare to return to Beirut this December, I carry with me the contrast between two cities: Toronto, where digital permits and AI-powered traffic lights ease daily life, and Beirut, where the absence of wide sidewalks and public libraries reflects deeper systemic gaps. These differences are not just about infrastructure; they are about equity, opportunity, and the kind of future we imagine for our children.

World Cities Day 2025 invites us to reimagine urban futures through the lens of “People-Centred Smart Cities.” But for this vision to be truly transformative, it must be rooted in the lived realities of children and caregivers in cities like Beirut, Bamako, and Port Vila.

It must recognise that smart cities are not only built with sensors and data but with empathy, inclusion, and justice.

Whether in the digital engagement platforms of Toronto or the community-led air quality monitoring in Dhaka, we see that smart cities thrive when they centre on people, especially children. They must be places where technology amplifies voices, where nature-based solutions restore dignity, and where every child, regardless of where they live, can grow up in safety, health, and hope.

This World Cities Day, let us move beyond aspiration. Let us commit to building cities that are data-informed but community-driven, technologically advanced but environmentally sustainable, and digitally connected but socially inclusive. Let us make smart cities truly work for children, for caregivers, and for the future we all share.

Learn more about World Vision’s work in urban areas.

Aline Rahbany is a global lead on urban programming at World Vision International. She brings 18 years of international development expertise focusing on supporting programs and strategies in countries faced with urbanisation risks and dealing with forced displacement and migration to cities. She has a Masters degree in Public Health (MPH), concentration on Health Education and Community Development, from the American University of Beirut (2008) and an Executive Masters in Cities from LSE (2025).