Malnutrition and Breast-milk Substitutes: A Threat to Cambodia’s Health and Economic Growth

Although proper nutrition during the first 1,000 days of a child’s life is essential for survival as well as overall health and wellbeing, malnutrition remains a serious problem for children in the developing world. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that under-nutrition is believed to be associated with approximately 2.7 million child deaths each year – nearly half of all child deaths globally. If malnourished children survive during their earliest years, they will likely face physical, cognitive, and developmental difficulties in the future.

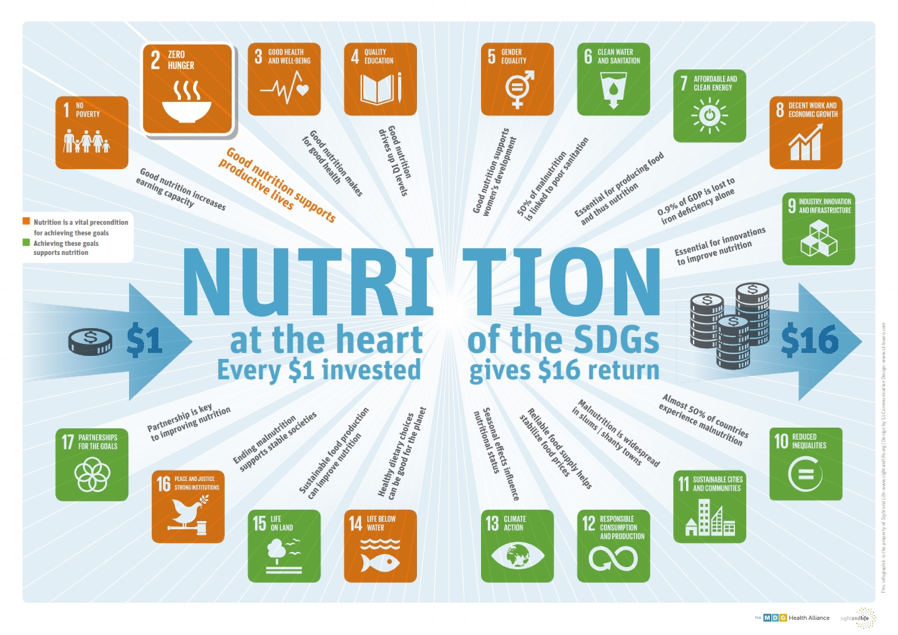

On a larger scale, economic growth is heavily dependent on proper nutrition. The United Nations recognize this fact in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which rely on the improvement of nutrition worldwide for the success of other objectives related to economics, health, and empowerment.

In the past several decades, Cambodia has made great improvements to infrastructure and industry, proving its resilience in the wake of war, genocide, and famine. Despite these advancements, the health and nutrition status of the country’s nearly 16 million people lags dangerously behind, threatening economic growth. Each year in Cambodia, more than $400 million is lost due to high rates of malnutrition and $200 million is lost due to micronutrient deficiencies. Approximately 57% of these economic losses are related to malnutrition in childhood.

One of the best ways to ensure optimal nutrition and health is to promote exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age and continued breastfeeding with supplemental foods until 24 months of age.

Research shows that these numbers are attributable to losses in workforce membership, child productivity, adult productivity, and healthcare costs. Specifically, developmental consequences from maternal malnutrition, suboptimal breastfeeding, low weight for height, low height for age, low weight for age, deficiencies in zinc and vitamin A, childhood and adult anemia, and birth defects can prevent workers from attending work when they are sick and from contributing their best efforts when they are present. Conversely, when Cambodian workers are attendant and healthy, outputs increase and expenses are retained. In this case, the government could expect millions of saved funds for future investments in infrastructure, industry, and social programs.

One of the best ways to ensure optimal nutrition and health is to promote exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age and continued breastfeeding with supplemental foods until 24 months of age. Breast-milk provides young children with both the nutrients to grow and the antibodies necessary to fight infection and disease. In fact, the WHO estimates that improving global rates of breastfeeding could prevent 820,000 deaths of children under the age of five every year. Yet, many factors prevent mothers from breastfeeding, including social pressures, aggressive advertising from breast-milk substitute (BMS) companies, and few rules requiring mothers to take maternity leave.

The solution can be so simple – invest in breastfeeding and nutrition.

Cambodia has fairly low rates of exclusive breastfeeding and high rates of BMS use. Only 65% of Cambodian children aged 0-5 months are exclusively breastfed, and an analysis of three recent Demographic and Health Survey reports shows that BMS use nearly doubled between 2000 and 2005 until leveling off slightly in 2010.

In response to this, the Cambodian government passed Sub-Decree 133 to regulate misleading marketing from BMS companies. Efforts like this are important, but alone they are not enough to fight the power and influence of the BMS industry. In 2014, it was reported that baby milk formula tallied $44.8 billion in total global sales with those numbers expected to reach to $70.6 billion by 2019. Comparatively, it was estimated in 2012 that the world suffered $300 billion in economic losses from poor health outcomes associated with mothers not breastfeeding their children. This reflects a severe need for further regulations and coordinated programs to better address BMS use and malnutrition worldwide.

The solution can be so simple – invest in breastfeeding and nutrition. The WHO and UNICEF recently reported that for every $1 invested in breastfeeding initiatives, $35 is returned in economic growth thanks to a smarter, healthier, more productive workforce. These investments will close the sociocultural, education, and policy gaps contributing to this complex problem and ensure healthier, more productive generations.

- Bagriansky, J., Champal, N., Pak, K., Whitney S., & Laillou, A. (2014). The economic consequences of malnutrition in Cambodia, more than 400 million US dollar lost annually. Asian Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 23(4), 524-531. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.4.08. Retrieved from: http://apjcn.nhri.org.tw/server/APJCN/23/4/524.pdf.

- CARD, UNICEF, & WFP (2013). The Economic Consequences of Malnutrition in Cambodia: A Damage Assessment Report [PDF]. Retrieved from: https://www.wfp.org/sites/default/files/Report%20on%20Economic%20Consequences%20of%20Malnutrition%20in%20Cambodia.pdf.

- Central Intelligence Agency (n.d.). World Factbook: Cambodia. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/cb.html.

- The Demographic and Health Survey Program [DHS] (2014). The Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey [PDF]. Retrieved from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR312/FR312.pdf.

- Global Breastfeeding Collective (2017). Nurturing the Health and Wealth of Nations: The Investment Case for Breastfeeding [PDF]. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-collective-investmentcase.pdf.

- Moench-Pfanner, R., Silo, S., Laillou, A., Wieringa, F., Hong, Rathamony, Hong, Rathavuth, Poirot, E., & Bagriansky, J. (2016). The Economic Burden of Malnutrition in Pregnant Women and Children under 5 Years of Age in Cambodia. Nutrients, 8(5), 292. doi: 10.3390/nu8050292.

- Prak, S., Dahl, M.I., Oeurn, S., Conkle, J., Wise, A., & Laillou, A. (2014). Breastfeeding Trends in Cambodia, and the Increased Use of Breastmilk Substitute – Why Is It Dangerous? Nutrients, 6, 2920-2930. doi: 10/3390/nu6072920.

- Rollins, N.C., Bhandari, N., Hajeebhoy, N., Horton, S., Lutter, C.K., Martines, J.C., Piwoz, E.G., Richter, L.M., & Victora, C.G. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387, 491-504. Retrieved from: http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(15)01044-2.pdf.

- Scaling Up Nutrition Civil Society Network [SUN CSA] (n.d.). Implementation of the SDGs at the National Level: How to Advocate for Nutrition-Related Targets and Indicators [PDF]. Retrieved from: http://docs.scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/SDGs-AdvocacyToolkit-En-final.pdf.

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, & International Baby Food Action Network (2016). The Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes: National Implementation of the International Code Status Report 2016 [PDF]. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/206008/1/9789241565325_eng.pdf.

This article is written by Madeleine Nicholson, an international intern at World Vision.