Community Health Committees

Community Health Committees

Community participation is essential in improving community health outcomes, and community participation is also understood as a vital element of a human rights-based approach to health. Ministries of Health (MoH) and governments have developed community health strategies that include a variety of forms of local participation, to include processes of community mobilization, the work of Community Health Workers (CHWs), and the functions of community health groups.

The COMM model focuses on the latter – strengthening community health groups to contribute to health outcomes. From raising money in Cambodia for the purchase of an emergency transport vehicle to building a washing center in Zambia at a health facility for women after giving birth, Community Health Committees are vital to making important contributions to health and fullness of life of the populations they serve.

COMM programming aims to work with Ministries of Health to improve support for Community Health Committees (CHCs) and Health Facility Management Committees (HMFCs), strengthening the capacity of these groups to identify and respond to important health issues in their area - including those of the most vulnerable and marginalized - thereby contributing to overall community-health systems strengthening, community capacity and equity, and improved overall health outcomes.

WHAT IS THE COMM PROJECT MODEL?

COMM involves the capacity building and empowerment of local health committees to coordinate activities leading to increased community capacity, an improved health policy and service environment and enhanced support of Community Health Worker (CHW) programmes, which collectively lead to strengthened community health systems and positive health outcomes.

The COMM model may be carried out through CHCs, HFMCs or other appropriately identified community health groups. CHCs around the world are typically embedded in the community and carry out their work there, are comprised of membership almost exclusively from within the community, and may or may not have a strong formal link with the health facility and the MoH at large. Their roles and responsibilities generally relate to identifying and addressing health issues within the community, as well as supporting CHWs and/or other volunteer health cadres. They may also be involved in actions of a social accountability nature, raising issues regarding health service performance.

HFMCs are by definition attached to local health facilities and formally linked with MoH, usually including both community representatives and facility staff as members, and typically hold meetings and carry out their work at the facility, often with less presence in the community as compared to CHCs. Roles and responsibilities may relate more to facility management concerns and the channeling of community health concerns to facility staff, than to work in the community as such. COMM programming may work with either type of group.

COMM is normally implemented in partnership with the MoH. A front-end programme functionality assessment is carried out to ensure that the contextual factors necessary for programme success are in place. The capacity of COMMs is then strengthened by WV and/or MoH staff using a suitable MoH curriculum or the WV-produced package of materials. Staff then support the COMMs in their community activities and monitor the results.

IMPLEMENTATION AND SCALE

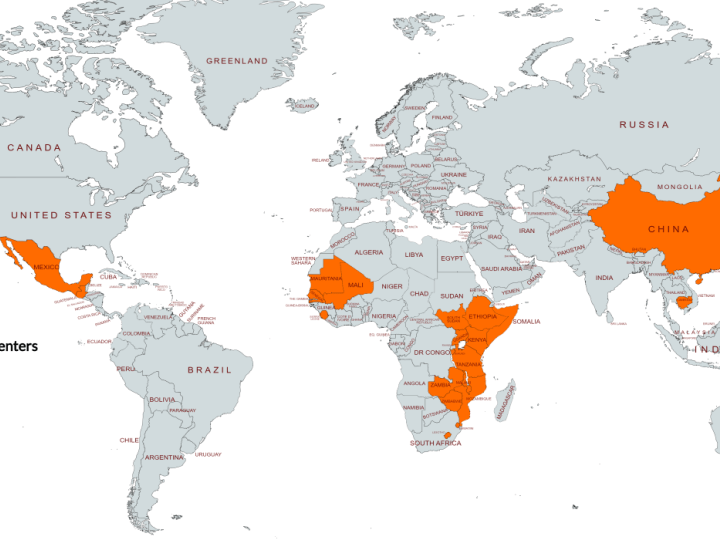

At least 21 field offices have implemented or are currently implementing the COMM model as of 2021 , working with at least 2,000 COMMs.

COMM Implementation Map

CORE COMPONENTS OF THE COMM PROJECT MODEL

Country Readiness: Ideally, COMM programming will be implemented within the MoH system, through MoH-linked CHCs or HFMCs (all known internally as ‘COMM’, although the original name of the group on the ground is always retained). Numerous decisions around the parameters of this programming must be taken together with the MoH, and therefore partnership and agreements with MoH must be established before implementation can begin. A national-level programme functionality assessment process is carried out together with the MoH using a specified tool which describes 14 components required for successful programming, and development of an action plan to address the areas assessed as weak. Certified COMM trainers from WV and/or the MoH will then run a training of facilitators (ToF) to prepare identified individuals to work with COMMs.

Getting started and training: As work with COMMs themselves commences, facilitators will ensure that the COMM’s membership is broadly representative of all community stakeholders, to include appropriate gender balance and representation of the most vulnerable and marginalised. An appreciative assessment and gap analysis of the group is carried out to understand their existing roles and responsibilities and trainings received to date, and to determine additional capacity building needs. Trainings are then carried out accordingly.

All COMMs receive a health information training shortly after programme start up, as well as a mandatory session on safeguarding and child protection, and then receive health-specific training and organisational capacity building support on an as-needed basis per the gap analysis results. This may be supplemented with trainings in additional content areas to include WASH, adolescent health, child marriage and more, to enable the broadening of the COMM’s scope of action outside of the health sector to include a more comprehensive range of issues. The COMM will additionally be brought into local level advocacy where this programming is being implemented.

ONGOING SUPPORT TO COMMS:

As COMMs begin to carry out their work, facilitators from WV and/or MoH will provide mentoring support and will track the COMMs’ progress with select indicators incorporated into an overall monitoring system.